|

In Ma Rainey's Black Bottom, that moment when Ma Rainey (Viola Davis) says, "They don't care nothing about me, all they want is my voice." Then the long moments she stands with her nephew Sylvester (Dusan Brown) as he stutters through the intro for her song, insists on take after take until he gets it right, while the white managers get impatient about what the retakes will cost them. Then the moment where (spoiler alert) Sylvester does it—he goes through the spoken introduction without a stumble—and Ma Rainey picks up the song without missing a beat, but a wide, mischievous smile.

This was Ma Rainey showing her relational care for her nephew. Not just so that he would earn some money, but because she wanted him to get the experience of having done it. She was letting him know that she had faith in him, his gifts. A very different affective structure than the one in which white men used her talents for their own profit. As Ma Rainey sings the rest of the song, Sylvester breaking out in a small dance: relief, pride. After the song is done, she applauding him—delighted hug: "See, I told you you could do it!"

0 Comments

(This essay appears on Periodicities: a journal of poetry and poetics. It is part of a 3-part project on visionary poetics, of which part 1 is here and part 2 can be heard here.) Vision And Knowledge“Poetry became an adventure. The finest of human adventures….Its goal: vision and knowledge.” —Aime Cesaire Perhaps it is because we live in a time of so many unknowns that now, more than ever, gives a call for our opus to become an adventure that flings open portals for vision and knowledge.

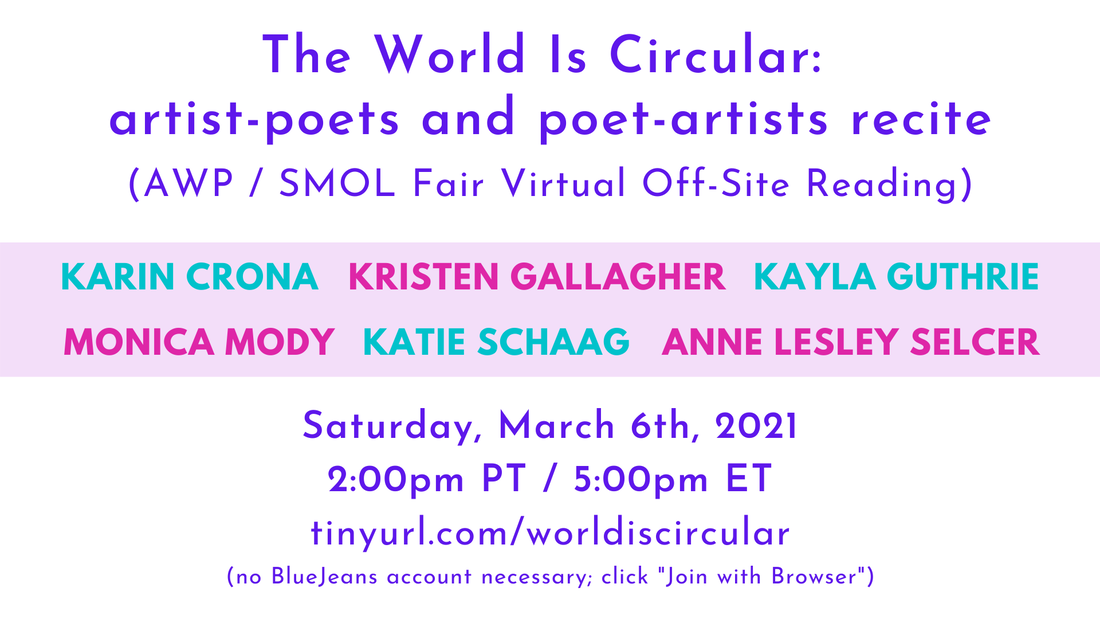

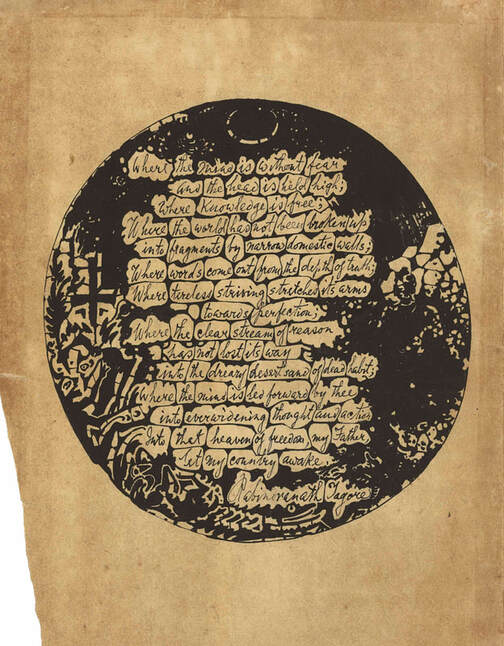

In this open place, remembering and imagination draw back from harsh borders where each abruptly ‘ends’ and the other ‘begins.’ The present knows itself to be shaped by pasts and futures even as it emerges with them. Pasts and futures have knowledge for those inhabiting the present even as denizens of the present are responsible to them. The task of reimagining and reconstructing pasts is not a tertiary one in the palimpsestic present. It is necessary so that futures may grow strong roots. The past shows the future its sharp glistening hunger—and healing futures nourish the hunger of the past. Past as ancestral memory sends visions of healing into the future. Futures are continually being shaped by pasts—just as the pasts are being reshaped and reimagined to open up futures before us. The entanglement of pasts and futures in visionary perception reveals linearity as but a flickering moleculate—a link. Inhabiting this fluid realm becomes possible as a result of our capacity to imagine. Imagination allows reality to become more than the density of reality determined by dominant perception. In contrast, the dominant mode of Cartesian-Newtonian dualisms conscripts our inner/outer movements into boxes or categories. Colonization of the mind by philosophies rooted in separation teaches humans to see Earth and body, emotion and instinct and intuition, dream and vision as inferior or naïve sources of knowing. These very forces are—in the epistemological universes of people of culture—regarded as sources yielding knowledge about the full spectrum of relational human experience. “What counts as knowledge is crucially important across human cultures precisely because what counts as the known usually helps define positions within the culture on questions central to human existence on the earth,” says Jane Duran. The loss of these other epistemes in modernity has resulted in a narrowing of our collective imagination about the Earth and each other. Our human pursuits have come to be driven by a Promethean impulse that sees itself as separate from and needing to tame nature. Diane di Prima reminds us that “the war is the war against the imagination,” and that this is a spiritual battle. Colonialist-imperial-capitalist-patriarchal matrices have always known it is our forgetting that will establish their sway. What we forget we are in relation to becomes vulnerable to being exploited or razed down. Without the remembering of interconnectedness, binary modes play into a politics of disenfranchisement, of dislocation. Disconnection is an age-old tactic for inducing traumas practiced by systems of domination. Then, reconnecting ourselves to vision and imagination becomes a political act. By extending ourselves in a stance of openness and radical hospitability to sources whose knowing (of life) has been silenced, marginalized, or invisible, we assert that we will no longer endorse the tactic of disconnection—or our own alienation. In Gloria Anzaldúa’s telling, Coyolxauhqui will not stay fragmented: her very fragments are filled with a desire for connection, reconstitution, healing. Imagination is key to her processes of integration. “You use your imagination in mediating between inner and outer experience,” says Anzaldúa. After Coyolxauhqui dismantles her old body/self, she re-composes a new body/self whose connective sutures hold nodes of new insights and possibilities for connection. The body holds an innate awareness that intimacy and alliances break open trauma paradigms. When bodies dream—bodies made of seeds and grains and sun and rain and dung—when this dreaming begins to speak—it exposes the subskeletal connections to life, to all of reality. What has been broken begins to link to each other: to heal. We dream so that the yet unrecognized may come into being. We slip out of the stranglehold of dominant reality and weave a reality from the fibrils of our dreams. Dreams and visions move us out of collective amnesia. They are the dark matter that allows reality to shift. They emerge from precisely the fissures structures of domination do not understand. Their very process is alchemical. The dissolution, re-membering, fluidity of becoming we encounter in visionary space can transform every aspect of our lives. Visionary imaginary takes us beyond the hegemony of modern/colonial pregivens to usher processes of decoloniality. As adrienne maree brown puts it, “Our radical imagination is a tool for decolonization, for reclaiming our right to shape our lived reality.” Making the future asks of us willingness to cross the threshold between visions and reality—nimbleness—uncontainability. This crossing is familiar, in a way, to artists. Dreaming and artmaking have much in common. “Working at art is so much like dreaming, sometimes I don’t know which is which,” says Denise Levertov. “True poetry,” says Cesaire, appeals to the unconscious—“the receptacle of kinship that, originally, united us with nature.” Thus in its shaded tongue “modest, secret” visionary truths can come forth. Yet what we are calling in is something more than can be contained by the definition of art. We are calling in a “consciousness of making / or not making your world”—a poetics, to quote di Prima—“no matter what you do.” What we are calling in is seeing. Remembering and imagination are modes of seeing. Seeing entangles us—we can no longer be on the outside looking in upon the spectacle of the real. Seeing, we acquire the power to transform it. Visioning is very much a relational mode. The visioning mode plucks us out of the mode of epistemic dependence that the dominator paradigm promotes. Taking full responsibility for what we see—through remembrance and imagination—transforms us into sovereign beings. The step that comes after is trusting what the vision is pointing to and taking pragmatic action. As Patricia Hill Collins reminds us, “the functionality and not just the logical consistency of visionary thinking determines its worth.” Actions link our visions to the ongoing struggle of transforming reality. The failure of the reality we live in is an ask upon us. Creating a different reality for ourselves, our children, ancestors, civet and trees and oysters and oceans is our task. Will we, then? Forge real relationships with extraordinary dimensions—with ecological realms or agency—storehouses of memory and visionary futures? Will we risk univocity and rational stakes—fluency and cognicentrism—guardedness and certainty? Will we proliferate beyond our own knowing, ego’s conceit? Will we pay attention to the ancestors? Will we speak from our hooded bodies, speak with stones—sibyl in frequencies such that speech swells and spills outsides the spectrum of normality? Will we light ourselves with our visions, prophesize the worlds we most want to see? The World Is Circular: artist-poets and poet-artists recite (AWP / SMOL Fair Off-Site Reading)3/2/2021 Karin Crona, Kristen Gallagher, Kayla Guthrie, Monica Mody, Katie Schaag, and Anne Lesley Selcer read new work.

This reading is hosted on BlueJeans. No account necessary. When you click the link, BlueJeans may prompt you to download the app; you can cancel and click "Join with Browser" instead. https://tinyurl.com/worldiscircular Meeting ID: 474 672 400 Passcode: 5744 Note: For security, the event will lock after 15 minutes (at 5:15pm ET). Be on time! Reader Bios The imprint of wholeness that is within us—within our DNA—is inalienably always there. Nothing can take it away, make it go away. If so, that sense of connection that coheres us with the Earth/Mother does not disappear. No matter how devastating, how total the severance seems to be. I am thinking of ghost limbs, which continue to feel sensation and transmit this information even after the physical limb is gone. I am thinking of tree stumps whose neighbors continue to transfuse nutrients and minerals to them. And, if so, even when egregious harm has been done (sexual violations, torture, mass murders), the actors of harm—disconnected from their web and roots of being—can be brought back to a sense of connection. Because the imprint of connection, to wholeness, is within them. I ask how not to move further away from those that cause harm despite the urge to do so—how not to disconnect. Disconnection, I know, tends to push something/someone even more into the shadows where behaviors of harm find feast and shape. I ask myself this, having retracted, yesterday, my poems from an anthology whose editor, I just learnt, was named as having touched another poet inappropriately. The editor-poet has neither acknowledged nor made any amends for his sexual misconduct. I asked the publisher of the anthology, who is based in the UK, to think about the nuances of responsibility and justice that land in his corner. I ask myself this after challenging, as a feminist killjoy, the unexamined/out-of-touch/misogynist ideas of an Indian man I'd met via a dating site, around "typical Indian girls" and "Eastern style dressing and hair." I ask myself this even as the voices and freedoms of the peoples of India are being quashed by a state wielding unmitigated power, whose anti-democratic logic is being bought into by apologists, economic neoliberals, and nationalist-fundamentalists. I ask myself this after doing the emotional, intellectual, and spiritual labor of writing to a white woman poet who casually threw in an "ashram" while talking about literary festivals/retreats during a writing circle where I was the only nonwestern, non-white person. I wrote to her that I felt exoticized and othered and uncomfortable; I didn't tell her about the heat that arose in my body or that my thought right after she said "ashram" and even after I had interrupted her in the moment was that I now needed to prove I was not "exotic," that I belonged. A friend reminds me that I can tell people this is not mine to hold alone. That everyone sees what is happening, and I can tell the others in the circle to speak to it. How can I name with clarity a behavior or a string or pattern of behaviors as wrong, while still holding out for the possibility that the imprint of wholeness can reassert itself in wrongdoers? How can I/we hold wrongdoers to accountability? How can I/we ask that they step up to take responsibility, to account for the harm done? How can the wrongdoers step into taking responsibility remembering their own interconnectedness? I am thinking of restorative justice and practices, where those who have been harmed and those who have caused the harm come together to talk about needs, obligations, what amends are needed. I am thinking of Angulimala. I am thinking of post-oppositional approaches. We are them. They are us. Is it possible to move towards "them" not to become them, but to eat away at the distance produced artificially, painfully, systematically, structurally, discursively? To devour the distance—like Kali-Chamunda lapping up with her tongue the blood of Raktabija? What stopped the demons from multiplying was Kali devouring the blood, which on falling to the ground would have given rise to more demons. To devour the drop of blood that would become a demon asks of us a profound spiritual/ethical commitment. To love ourselves, to love the other.

It asks of us to expand our range of holding so that it includes human-shadow-divine, Life-Death-Life. We commit ourselves to nonduality from that place where all is known as included. It asks that we grow an unshakable sense of self that is embodied, that has the capacity to be present. That we are sovereign and restored unto ourselves. And this is where I notice the ways in which, despite the theory and the vision, I sometimes hide in my own life. I hide from people who I perceive will judge me. I hide from myself and the knowing that what I vision is possible. The journey to wholeness is both long and short, my friends. I am glad to have connected with you along the way. One can point to external recognition in bios for our metrics-oriented culture, but when you want to evoke the feltness in your life, the internal milestones, those that (be)came in your moving through the tenuousness and ruptures—the succinct always has a shortfall.

|

Get updates of New blog postsconnect with me ON SOCIALSArchives

April 2024

|

RSS Feed

RSS Feed